Ticks in South Carolina

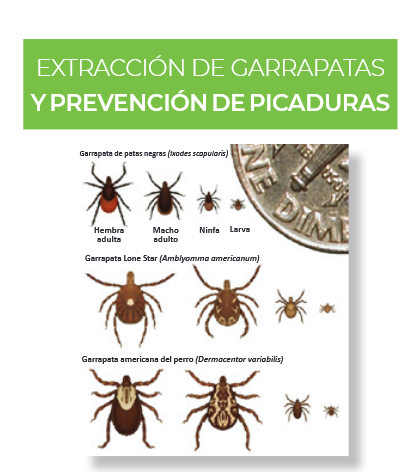

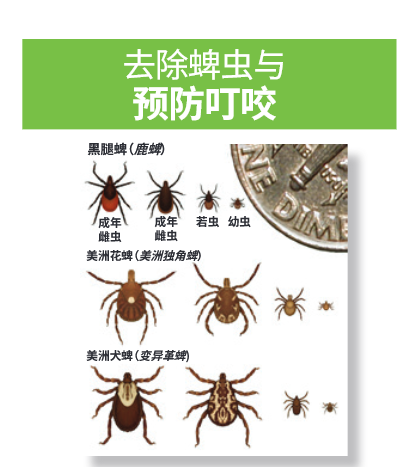

Ticks are external parasites that go through four developmental life stages: Egg, six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph, and adult. Ticks must attach and take a blood meal from animal hosts to grow and develop into the next life stage or to produce offspring. In South Carolina, people often encounter six tick species: the blacklegged, lone star, American dog, brown dog, Gulf Coast, and Asian longhorned ticks. Tick bites and tick-borne disease can occur year round. Ticks are generally found near the ground in forests and in areas with brush or tall grass and weeds. Ticks cannot jump or fly. Instead, they climb tall grasses or shrubs and wait for a potential host to brush against them. This behavior is known as “questing.” When this happens, they climb onto the host and seek a site for attachment.

Ticks and Associated Tick-Borne Diseases or Conditions

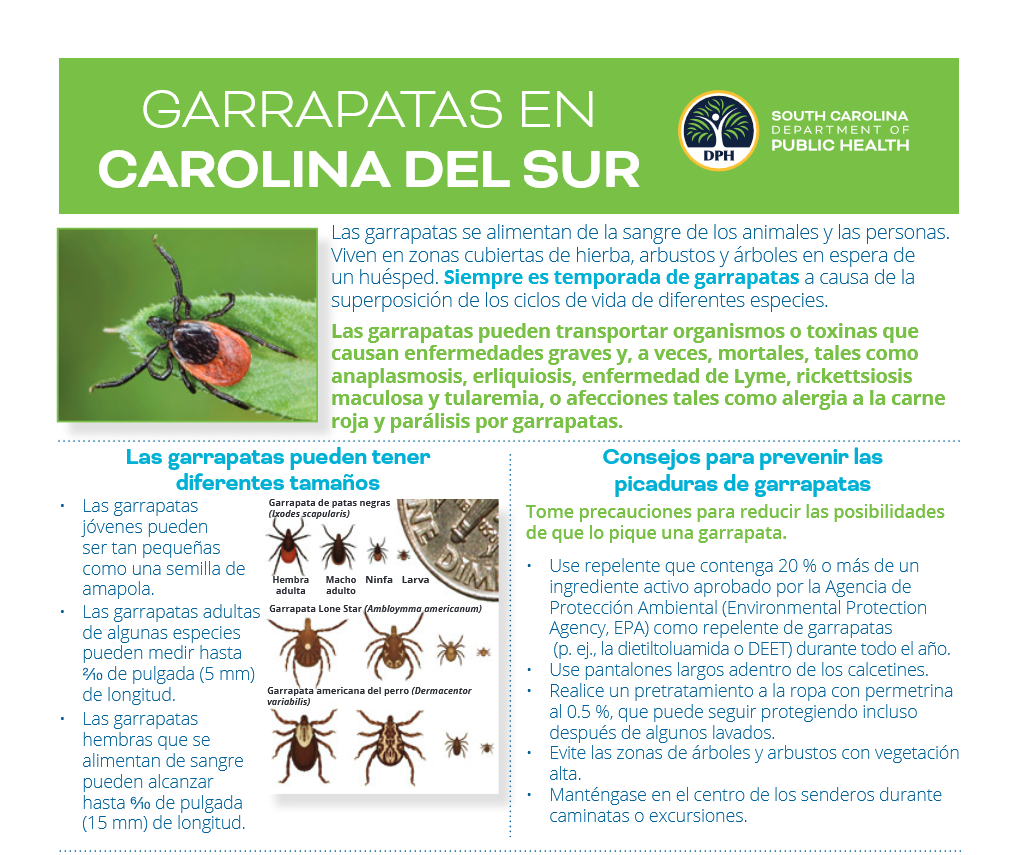

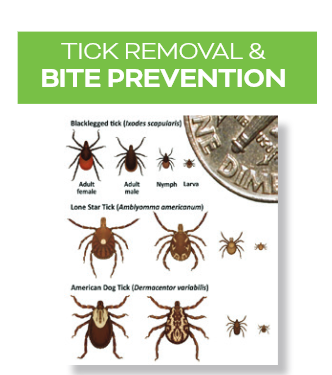

Lone Star Tick

- Ehrlichiosis, Heartland virus, red-meat allergy, Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness (STARI), spotted fever group rickettsiosis, and tularemia

*Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

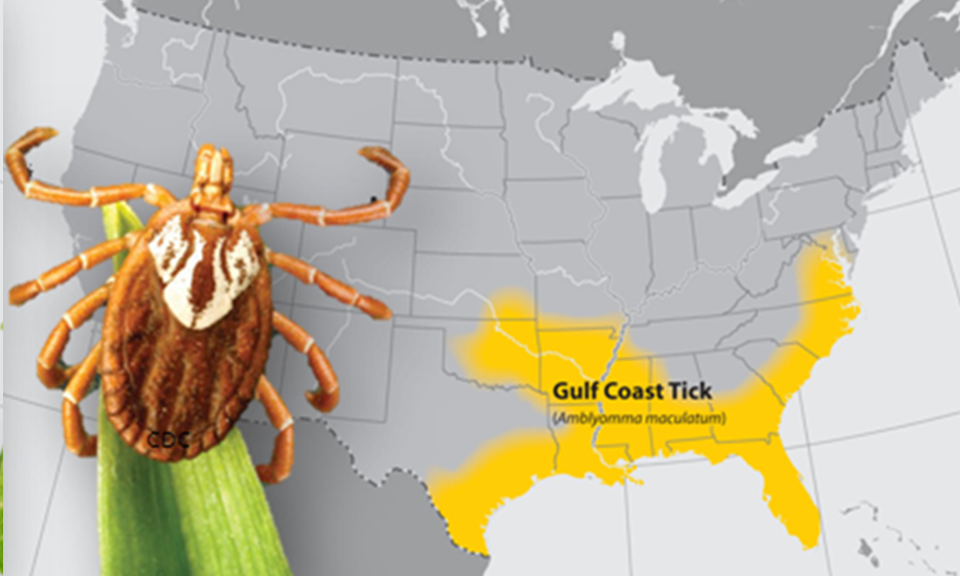

Gulf Coast Tick

- Ehrlichiosis, spotted fever rickettsiosis, and tick paralysis

*Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

American Dog Tick

- Ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), tick paralysis, and tularemia

*Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

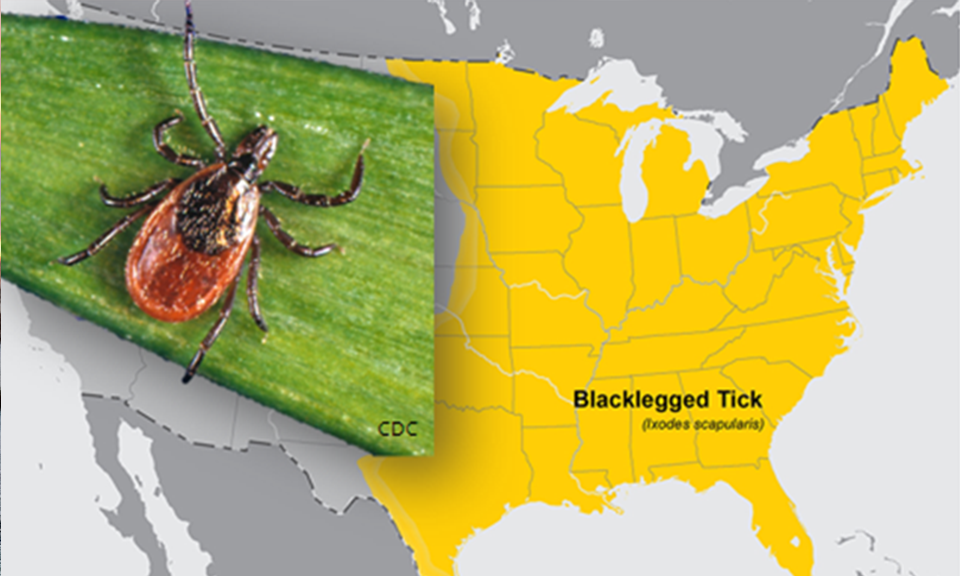

Blacklegged Tick

- Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, Lyme disease, Powassan virus disease, and red-meat allergy

*Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Brown Dog Tick

- Ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and tularemia

*Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

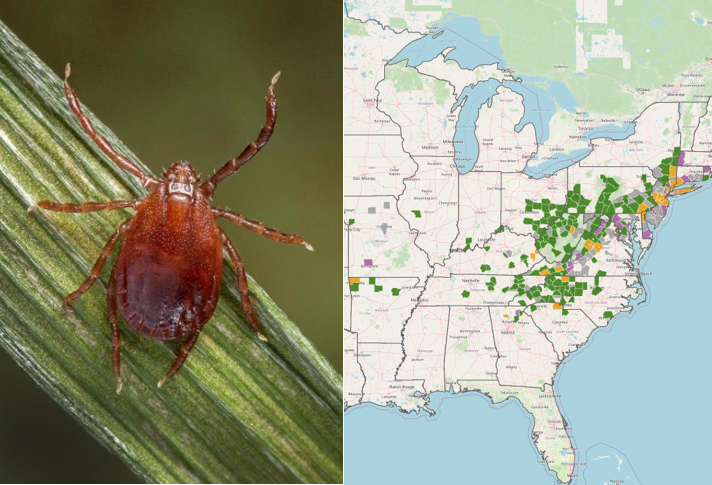

Asian Longhorned Tick

- Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Heartland virus disease, Powassan virus disease, and cattle theileriosis (Theileria orientalis Ikeda strain).

*Image courtesy of the United States Department of Agriculture – Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Tick-Borne Diseases and Conditions

Ticks can carry and transmit a multitude of pathogens that may result in contracting a tick-borne disease, including: anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Lyme disease, Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness (STARI), ehrlichiosis, Powassan virus disease, Heartland virus, and tularemia. In addition to tick-borne diseases, a toxin can be transmitted through the saliva of a tick bite that causes progressive paralysis, a condition known as “tick paralysis.” Tick feeding also may result in mild to severe allergic reactions in some individuals.

Heartland virus

Heartland virus disease is caused by a virus in the genus Bandavirus,family Phenuviridae. Symptoms begin within a few days to two weeks after a tick bite and may include fever, fatigue, decreased appetite, headache, nausea, diarrhea, and muscle or joint pain.

Lyme disease

Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia bacteria that is transmitted after a tick has been attached and feeding for 24-72 hours. Symptoms begin within days or weeks after a tick bite and may include fever, headache, chill, stiff neck, fatigue, muscle aches, and joint pain. An expanding red skin rash called an erythema migrans (EM), which grows at a rate of ½ to ¾-inches per day at the site of the tick bite, occurs in 70-90% of patients. The EM rash is typically around 6 inches in diameter but can reach 8-16 inches. A red rash with a central clearing, known as a bull’s eye rash, is characteristic of older rashes and is present in less than half of all cases. The EM rash should not be mistaken for a local allergic reaction to the tick bite which typically lasts for 2-4 days; redness caused by an allergic reaction will have shorter duration and expands at a slower rate than an EM rash. People who are hypersensitive to tick bites may have an immediate, intense reaction that is not an EM rash.

Powassan virus

Powassan virus disease is caused by Powassan virus (lineage 1) or deer tick virus (lineage 2) in the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae. Initial symptoms begin within 1 week to 1 month after a tick bite and may include fever, headache, vomiting, and weakness. Powassan virus can cause severe disease, including inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) or the membranes around the brain and spinal cord (meningitis). Symptoms of severe disease include confusion, loss of coordination, difficulty speaking, and seizures. Approximately 1 out of 10 people with severe disease die. Approximately half of the people who survive severe disease have long-term health problems. These can include recurring headaches, loss of muscle mass and strength, or memory problems.

Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses

Spotted fever group rickettsiosis (spotted fevers), including Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), are caused by Rickettsia bacteria that are transmitted after the tick has been attached and feeding for 12-24 hours. Symptoms typically begin from 5-7 days (range 2-14 days) after a tick bite and may include sudden onset of fever, headache, and muscle pain, and sometimes nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, appetite loss, and a spotty rash in 90% of patients. The rash usually is noticed first on the wrists and ankles before it spreads.

Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness or STARI

STARI results in a rash that begins as a red, expanding “bull’s eye” open sore at the bite site. The rash usually appears within 7 days and expands to a diameter of 3 inches or more. The rash may occur with fatigue, fever, headache, muscle aches, and joint pain.

Tick-borne Erhlichiosis and Anaplasmosis

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis are caused by Ehrlichia and Anaplasma bacteria that invade white blood cells. Symptoms usually begin 5-10 days after a tick bite and may include fever, headache, joint pain, muscle aches, nausea, and vomiting. Two to 40% of patients develop a body rash, typically not involving the hands and feet.

Tularemia

Tularemia is caused by a bacterium,Francisella tularensis. Symptoms usually begin 3-5 days after the tick bite and may include chills, headache, coughing, muscle aches, vomiting, repeated spikes of severe fever, swollen lymph nodes that develop into skin ulcers in 80% of cases, conjunctivitis (pink eye), and pneumonia. A scab may develop at the bite site before flu-like symptoms occur. Symptoms may go into remission for 1-3 days, followed by return of the illness for 2-3 weeks.

Tick paralysis

Tick paralysis is caused by a neurotoxin produced in the tick's salivary glands. Symptoms usually begin within 2-7 days and may include headache, vomiting, general malaise, and loss of motor function and reflexes. Leg weakness progresses to paralysis and spreads upward to the rest of the body. If the tick is not removed, paralysis may lead to respiratory failure and death. Symptoms of paralysis and the discovery of the tick, usually on the scalp, are indicative of tick paralysis. Tick removal relieves symptoms within hours to several days.

Red-Meat Allergy (Alpha-gal Allergy)

Tick bite-induced red meat allergy is an allergic response to a sugar molecule (alpha-gal) found in most mammals. After a tick bite, eating red meat may result in itching, rash, swelling, gastrointestinal upset, and severe allergic reaction. Symptoms appear several hours after eating red meat (beef, pork, lamb, venison, and meat from any furry, warm-blooded creature) or other food products with animal connections [dairy, lard (rendered pig fat), and gelatin (made from boiling animal bones, skin, and tissue). White meat from poultry and fish does not contain alpha-gal and will not induce an allergic reaction.

Tick Bite Prevention

Attached ticks should be removed as soon as possible to prevent the transmission of possible pathogens. Disease transmission from ticks generally occurs within 24 hours or up to 72 hours after attachment, but diseases such as Powassan virus disease can be transmitted in as little as 15 minutes. In general, the longer a tick is attached, the more likely it is to pass on an infection if it is carrying one. Below are some general precautions that if used or performed properly can help prevent tick bites:

- Use Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus, para-menthane-diol, or 2-undecanone. Treat clothing and gear, such as boots, pants, socks, and tents with products containing 0.5% permethrin. Additional repellent options are available. EPA’s repellent search tool can help find the product that best suits your needs. Follow label directions.

- Wear protective clothing tucked in around the ankles and waist.

- Shower with soap and shampoo soon after being outdoors to reduce the possibility of tick attachment.

- Keep weeds and tall grass cut and avoid tick-infested places such as grassy and marshy woodland areas when possible.

- Stay in the center of paths when hiking or walking through woods.

- Check for ticks daily, especially under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and on the hairline and scalp.

- Check pets for ticks daily. Treat dogs and cats for ticks as recommended by a veterinarian.

- Learn more about landscaping techniques that can help reduce black-legged tick populations in your yard.

Tick Removal

- Never squeeze ticks or use heat, solvents, nail polish, petroleum jelly, or other material to make the tick detach from the skin. These actions often cause the tick to regurgitate fluids into the bite, increasing the potential for disease transmission.

- Use fine-tipped tweezers to remove attached ticks by grasping the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

- Pull upward with steady, even pressure while being careful not to jerk or twist the tick as this could cause the mouthparts to break off and remain in the skin.

- After removal, clean the bite area with soap and water and apply an antiseptic such as iodine, hydrogen peroxide, or rubbing alcohol.

- Write down the date of the tick bite to help monitor for potential symptoms.